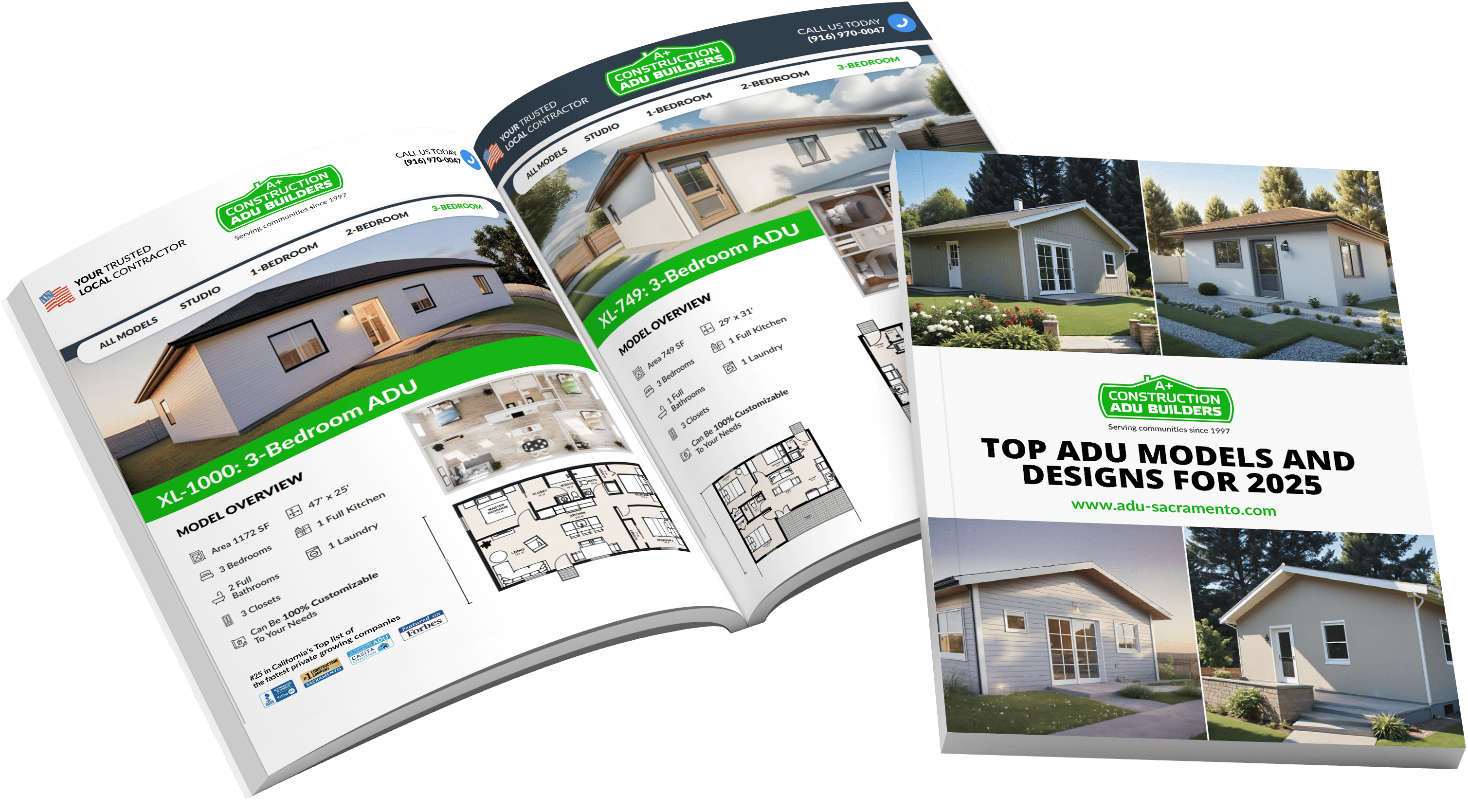

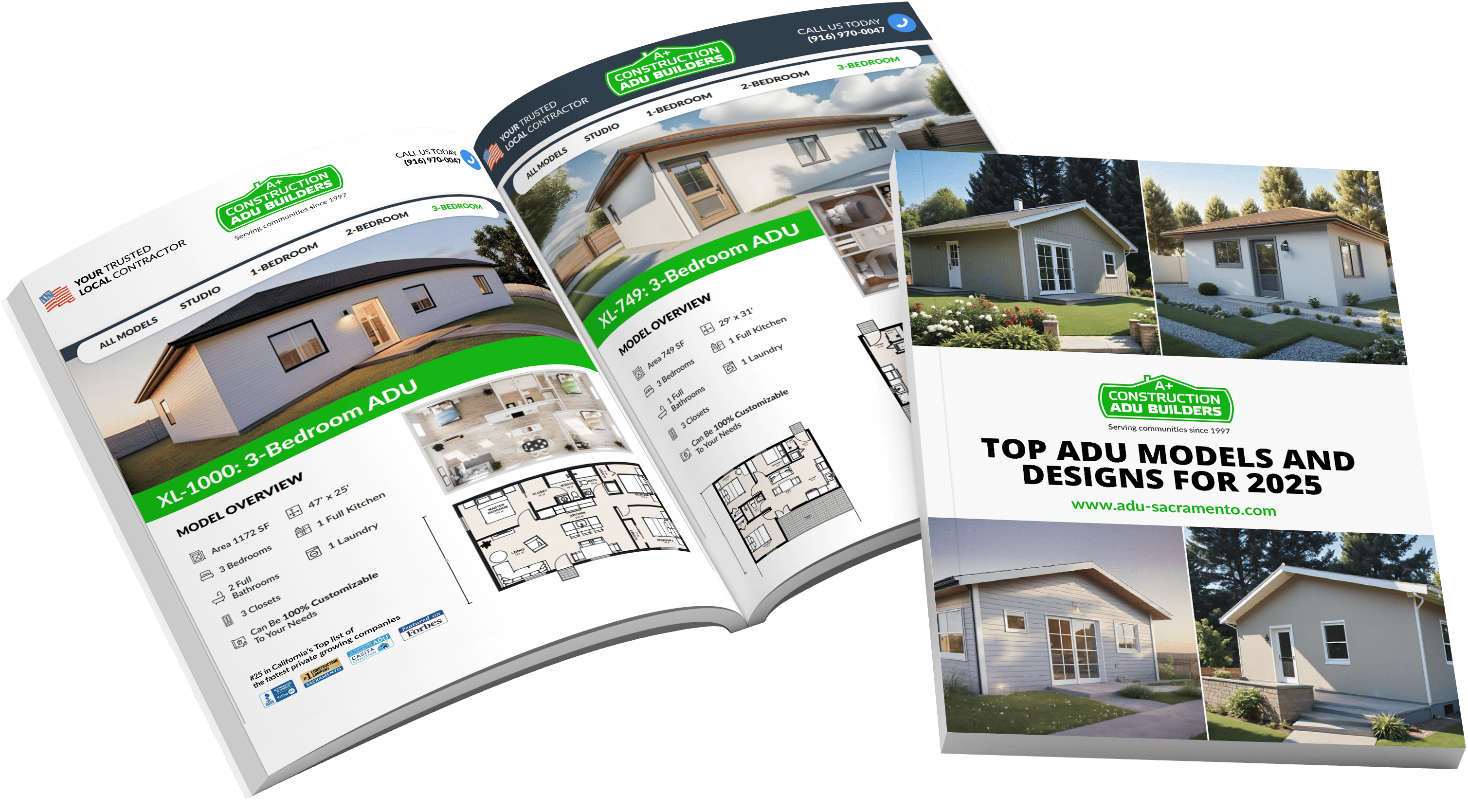

A link to download your FREE brochure will be in your inbox in 3 minutes

The final price may vary based on project specifics.

To get a free accurate quote tailored to your needs, book a consultation with us today!

The price per square foot provided is an average and may vary depending on project-specific details such as materials, location, complexity, and other factors. Actual costs may differ from the average provided.

It is recommended to obtain a detailed quote based on the specific requirements of your project.

Please note that the monthly payment displayed on this page is an estimate and is subject to variation based on the selected loan product, applicants credit score, loan amount, and other financial details. Actual monthly payment may differ from the estimate provided.

It is recommended to seek advice from a financial advisor or loan officer to obtain precise payment information tailored to individual circumstances.

Your Trusted

Local Contractor

Your Trusted

Local Contractor

What is SB 9? This abbreviation stands for Senate Bill 9, also known as the Home Act. It’s a California law passed as a measure against the housing crisis. SB 9 allows for two types of action with single-family residential lots: two-unit development (converting a primary dwelling unit into a duplex) and splitting the lot into two adjacent parcels (each one must be at least 1,200 sq. ft). If you split your lot in two, you’ll be able to have four buildings on it — two ADUs and two primary units (your existing single-family home and a new house). The main purpose of this law is to promote the construction of additional housing units and thus mitigate the effects of the housing crisis.

In our article, we’ll take a close look at SB 9 and its main distinctive features and compare it with accessory dwelling unit (ADU) construction.

SB 9 has several exceptions that can disqualify property owners from using it. Knowing these exceptions is essential for deciding whether the single-family lot split provision is a suitable variant for you or not.

They are the following:

Because SB 9 is a rather new law and exists only in California, the financial institutions in many cities don’t have sufficient experience in dealing with split property. This means that, sadly, you may have some problems with lending.

As we’ve already said, the SB 9 lot split provision requires a three-year owner’s occupancy. It means that the property owner has to live in the existing single-family home for three years from the moment of approval. Moreover, the law forbids ministerial approval of property splits on neighboring parcels by the same individual. This measure is meant to avoid possible speculations.

In addition to that, you can’t use SB 9 if a tenant lives on your property now or lived there in the past 3 years. This measure prevents displacing or evicting tenants from rental units.

If you start constructing a new primary dwelling unit on a lot created with SB 9, you’ll have to follow your local zoning rules. You’ll also need to do it if you’re turning your existing single-family home into a duplex — as long as those regulations don’t physically preclude two-unit developments. Moreover, if you want your lot splits to be eligible for optimization, you’ll need to construct a new unit there.

Also, it’s important to mention that many cities have parking requirements (such as constructing a garage). If you build an accessory dwelling unit (ADU), you can waive them, but in case of a main house, complying with them is necessary for completing the permitting process. Note that in many cities, those requirements change depending on the distance to the nearest major transit stop.

You’re probably trying to choose between these two affordable housing options and don’t know which one is better for you.

To help you, we’ve compared both variants and their main characteristics:

Note that some of the aforementioned things can be really expensive — for example, making utility connections on lot splits. You’ll need to connect them to the sewer and water pipes, which is super costly. Owner’s occupancy and the possibility of units being sold separately are also very important factors, which you’ll definitely need to take into consideration.

Using Senate Bill 9 can be risky because there are no such precedents in the affordable housing sphere yet. This California state law is basically an uncharted field with very few cases, so it’s still unclear how this law will work. Because of this, there are lots of gray areas here, and we can’t exactly say what interpretation they will have. All of this can lead to unpleasant consequences such as prolonged approval periods, additional expenses, and juridical difficulties. So, if you decide to apply SB 9 on your lot, be careful and remember that it probably won’t be easy.

Other potential challenges for property owners include:

Is it possible to build additional housing units on split lots created with SB 9? Yes, if your local government allows it. So, in many cities homeowners can have two accessory dwelling units and a primary unit converted into a duplex on one half, and the same configuration on the other. However, this varies depending on the local zoning laws, so it’s crucial to read them thoroughly or consult with a specialist before planning.

SB 9 (Senate Bill 9) is a rather new local law which allows California homeowners to split their property lots into two parts, or to turn their houses and duplexes. The main purpose of this law is to stimulate growth of the affordable housing market. An ADU (accessory dwelling unit) is an additional, smaller house built on the same lot as the main residence.

There are different types of ADUs: attached, detached, a junior accessory dwelling unit, a garage or basement conversion, and so on. The ADU law varies greatly depending on the local jurisdiction. Typically, the maximum number of ADUs on the same lot in California can be two: one ADU is regular and the other is junior.

According to the state law, SB 9 eligibility requires two following things. Firstly, your lot has to be in a city area or agglomeration. It is a strictly urban lot split. Secondly, its location needs to be in a single-family residential area.

Usually, a lot is split, including county/city permit fees and third-party vendor expenses, which cost $50,000-$80,000. However, there may also be some additional expenses. For instance, different “right of way” improvements, such as utility connections, can significantly increase the overall price.

The biggest size of any building on a split lot is 850 sq.ft.; meanwhile, the smallest is 800 sq. ft. The total area of both primary dwelling units (single-family homes) on the parcel shouldn’t exceed 1,700 sq. ft. As for the lot parts themselves, the maximum square footage of each one is 1,200 sq. ft.

Get a First Look at Real ADU Projects